Great megafauna mystery solved? Humans really did drive ancient giants to extinction

[ad_1]

Prehistoric humans hunt a woolly mammoth. More and more research shows that this species – and at least 46 other species of megaherbivores – were driven to extinction by humans. (CREDIT: Engraving by Ernest Grise, photographed by William Henry Jackson. Courtesy Getty’s Open Content Program)

AARHUS, Denmark — Imagine a world where elephants roamed across Europe, giant ground sloths lumbered through the Americas, and car-sized armadillos burrowed in South American grasslands. This wasn’t some fantastical realm from a Hollywood movie — it was Earth just 50,000 years ago. But then something happened. These megafauna — animals weighing over 100 pounds — began to disappear. By 10,000 years ago, most were gone forever.

What caused this mass extinction event that reshaped life on our planet? It’s a question that has puzzled scientists for over 200 years. Now, an international team of researchers has conducted an exhaustive review of the evidence, concluding that prehistoric humans were likely the primary culprits behind the downfall of Earth’s giants.

The study, led by scientists from the Danish National Research Foundation’s Center for Ecological Dynamics in a Novel Biosphere (ECONOVO) at Aarhus University, analyzed patterns of megafauna extinctions across continents and time periods. They found that large animals began vanishing shortly after humans arrived in new regions, with extinction rates highest where humans were most novel.

“The large and very selective loss of megafauna over the last 50,000 years is unique over the past 66 million years. Previous periods of climate change did not lead to large, selective extinctions, which argues against a major role for climate in the megafauna extinctions,” says Professor Jens-Christian Svenning, the study’s lead author, in a statement.

The researchers point out that climate change, long considered a potential cause of the extinctions, doesn’t adequately explain the patterns observed. While the late Pleistocene epoch did see significant climatic shifts, these were no more extreme than previous glacial cycles that didn’t result in mass extinctions.

“Another significant pattern that argues against a role for climate is that the recent megafauna extinctions hit just as hard in climatically stable areas as in unstable areas,” Svenning adds.

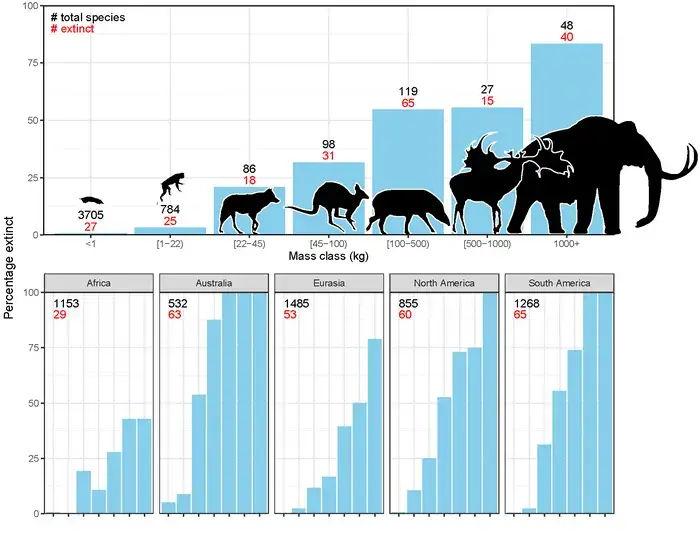

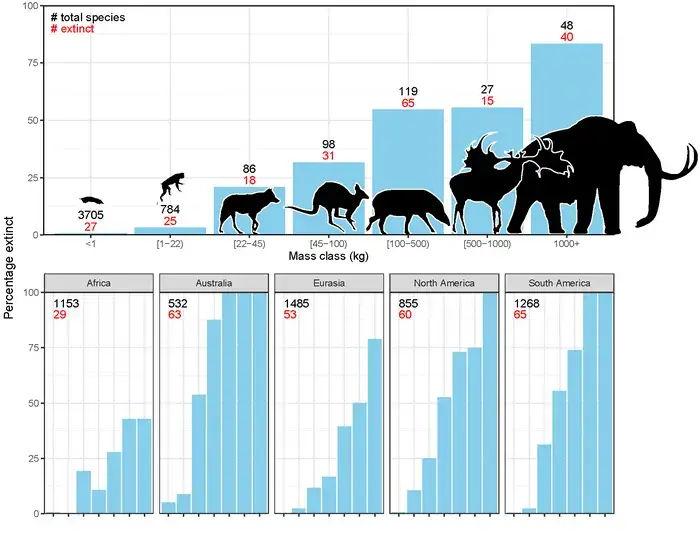

Additionally, the megafauna losses were highly selective, primarily affecting only the largest species. Smaller animals, plants, and marine life were largely unaffected. This size bias matches what we’d expect from human hunting pressure, not climate change.

The study reveals that at least 161 species of mammals were driven to extinction during this period, based on the remains found so far. The largest animals were hit the hardest — land-dwelling herbivores weighing over a ton, known as megaherbivores. Fifty thousand years ago, there were 57 species of megaherbivores. Today, only 11 remain, with even these survivors experiencing drastic population declines.

Interestingly, regions where humans had a longer evolutionary history with large animals saw less severe extinction events. In Africa and parts of Asia, where hominins had been present for millions of years, fewer megafauna species went extinct compared to the Americas and Australia. This suggests animals in Africa and Asia may have developed behaviors to avoid human predators over time. The researchers found evidence of human hunting prowess in the archaeological record.

“Early modern humans were effective hunters of even the largest animal species and clearly had the ability to reduce the populations of large animals,” notes Svenning. “These large animals were and are particularly vulnerable to overexploitation because they have long gestation periods, produce very few offspring at a time, and take many years to reach sexual maturity.”

The loss of these ecosystem giants had profound impacts that are still shaping our world today. Large herbivores like mammoths and ground sloths played crucial roles in maintaining open habitats and dispersing nutrients across landscapes. Their disappearance likely contributed to the spread of forests and changes in fire regimes in many regions.

“Species went extinct on all continents except Antarctica and in all types of ecosystems, from tropical forests and savannas to Mediterranean and temperate forests and steppes to arctic ecosystems. Many of the extinct species could thrive in various types of environments. Therefore, their extinction cannot be explained by climate changes causing the disappearance of a specific ecosystem type, such as the mammoth steppe – which also housed only a few megafauna species,” Svenning emphasizes.

The authors argue that understanding this extinction event is crucial as we face a biodiversity crisis today. By recognizing humans’ long history of impacting animal populations, we can better inform conservation efforts. They even suggest “rewilding,” reintroducing large animals to restore lost ecological functions, as a potential conservation strategy.

“Our results highlight the need for active conservation and restoration efforts. By reintroducing large mammals, we can help restore ecological balances and support biodiversity, which evolved in ecosystems rich in megafauna,” Svenning concludes.

The study is published in the journal Cambridge Prisms: Extinction.

Methodology

The researchers conducted an extensive literature review, examining evidence from paleontology, archaeology, genetics, and ecology. They analyzed patterns of megafauna extinctions across different continents, time periods, and body size classes. The team also evaluated various hypotheses for the extinctions, including climate change and human impacts, against the observed patterns. Their review incorporated several research fields, including studies on the timing of species extinctions, animal dietary preferences, climate and habitat requirements, genetic estimates of past population sizes, and evidence of human hunting.

Results

The study found that megafauna extinctions were global in scope but varied in intensity across regions. They were strongly biased towards the largest species and temporally linked to human arrival in new areas. The extinctions were not well-explained by climate change alone. The researchers observed that at least 161 species of mammals were driven to extinction during this period, with land-dwelling herbivores weighing over a ton (megaherbivores) being the most severely affected.

Limitations

Among possible limitations of this study, the fossil record is incomplete, especially for smaller species, which can bias our understanding of extinction patterns. The dating of extinction events and human arrivals can be imprecise, making it challenging to establish exact temporal relationships. Additionally, complex interactions between humans, climate, and ecosystems are difficult to fully disentangle, especially over such long time scales.

Discussion & Takeaways

The researchers conclude that human hunting and ecosystem modification were likely the primary drivers of late Quaternary megafauna extinctions. They argue this event marks an early example of human-driven environmental change on a global scale. The study emphasizes that humans have been shaping ecosystems for tens of thousands of years and that large animals are particularly vulnerable to human impacts. The loss of megafauna had cascading effects on landscapes and ecosystems, altering vegetation structures, seed dispersal patterns, and nutrient cycling. The authors stress the importance of understanding past extinctions to inform modern conservation efforts. They suggest that rewilding with large animals may help restore lost ecological functions and support biodiversity in ecosystems that evolved with megafauna.

[ad_2]

Source link